I get very excited whenever I have the chance to visit the Sonora desert because it offers a dizzying variety of subjects to shoot. My trips here also tend to be filled with bizarre phenomena, rare creatures and sometimes even death-defying experiences. The latter was the case with this trip anyway. I visited southeast Arizona during the first 2 weeks of August, 2023 to shoot a little bit of everything; monsoon lightning, reptiles, macro insects, sunsets and hummingbirds. I mainly came here for herping; taking photos of reptiles and amphibians.

I also enjoyed the freedom of living out of my truck for a few weeks. Ffind cool places to sleep, avoiding the heat of the day and staying hydrated added to the adventure. Along the way I traveled through the Chiracahua Mountains near Portal, the Huachuca Mountains near Sierra Vista, and all around Tucson. My friend Michael Routh of Dreamchaser Visuals from California joined me. The desert did not disappoint; this trip was an exciting odyssey filled with natural wonders and mysteries around every turn.

The Sonora Desert is fascinating because it conceals so many natural anomalies. To name a few, the Sky Islands are isolated mountain ranges that pierce the hot desert. As their name implies, they harbor unique life on their lush peaks that’s different from the desert below. Five eco-regions with a huge biological diversity overlap in southeast Arizona. This, along with disparate climates between elevations creates an abundance of niches, which gives Arizona greater biodiversity than any other same-sized region in the US.

Monsoon Thunderstorms in the Sonora Desert

While on a nocturnal walkabout through the Saguaros in search of wee beasties, this cumulonimbus cloud materialized and began casting magic. Moments before, thin clouds gave no hint that electrical Godzilla was about to rise. It moved north so quickly that I only fired off 3 shots before it was out of frame, but that was enough.

The Arizona monsoon thunderstorms are a reliable summer event. They happen because in summer air currents shift from moving in from the dry west to appraoching from the south, laden with moisture they picked up from the Pacific Ocean. When the moisture hits the strong thermals of hot air rising off the desert, it’s pushed high into the atmosphere. There, it meets cold air, condenses into storm clouds and rains down. Monsoon storms are crucial to the Sonora Desert because virtually all life synchronizes their reproduction around them. They bring most of the year’s rain.

In August, the atmosphere in the Sonora desert is radiant with the churning of nature. Catalina State Park on the NW edge of Tucson is an exemplary slice of Saguaro desert scrub, framed by the Santa Catalina Mountains. When I visited, monsoon storms were brewing in two directions during golden hour. The light pierced through thunder clouds and flickered over the lime-green landscape. I wanted to consume the beauty with my eyes, and I suppose my camera is the mouth of my vision. Nearby lightning bolts and cracking thunder made my nerves tingle. A welcome breeze of cool air washed over me after standing in the 105° F desert inferno. My shoot was abruptly ended when rain drops large enough to make “splats” instead of “patters” began to fall.

- This is 2 composite shots of a thunder cell near the Santa Rita Mountains south of Tucson

Rattlesnakes in the Sonora Desert

The Sonora Desert has the most rattlesnake species in the US, and an impressive diversity of other reptiles. People often think this is because reptiles like hot weather, which isn’t really true. It would be fatal for most Sonoran reptiles if forced to remain exposed in the summer sun. Reptiles are cold-blooded meaning they can’t regulate their body temperature internally like we can. This is why most species are nocturnal in summer. If the temperature exceeds the ideal range, their only way to cool down is by moving into shade. If they get too cold, they can’t move or digest food. So it’s not that they love high heat, but it’s advantageous to live someplace with constant access is to heat in the right doses.

- The Western Diamondback Rattlesnake is the Sonora’s most common rattler

Tiger rattlesnake venom is a mixed drink of neuro and hemotoxin, meaning it first paralyzes prey, then digests it. There are so few recorded human envenomations from Tiger Rattlesnakes that we don’t know what the typical effects are. It’s hard to get bit by these small rattlers because they average only 24″ with a strike distance of about 8″. Despite its standing as the 3rd most venomous snake in the New World, apparently only enough venom is delivered to subdue a mouse. There were no lasting effects in the few people that were bitten, but I still wouldn’t chance it without care. In large doses, the neurotoxin causes paralysis in muscles like the diaphragm and heart.

In my worldview, rattlesnakes are virtually harmless. Most people don’t understand how I deliberately search for them without repeatedly being killed. This perception probably stems from the assumption that a long slender creature with a weapon of mass destruction on its head will bolt after you like a spear. In reality, rattlers are among the slowest moving snakes and don’t chase. They instinctively know they’re tasty treats for owls, roadrunners and coyotes, so they tend to slither in the opposite direction of danger. When coiled, rattling and primed to strike, rattlers are probably in their least dangerous posture for humans because they’re just a pile of snake that’s easily seen and avoided. Even then they usually don’t strike unless seriously cornered or harassed.

Rattlers prefer to save their venom for hunting, not biting big things they can’t swallow. You’ll no doubt have a bad day if you step on one barefoot walking through the grass. Or if for some reason you put your hand within striking distance. However, if I were forced to sit in a chair in a pit of rattlesnakes, my biggest fear would be not having something interesting to read. Granted, it might be a little challenging when had to get up and use the restroom, depending on how many snakes there were.

The Mojave Rattlesnake has by far the most deadly venom of any rattler, rivaling the neurotoxicity of Cobras. However, some populations in distinct geographic regions have venom that’s ten times less toxic than other Mojave Rattlesnakes.

The small Sidewinder moves by throwing a loop of its body forward, then drawing the rest behind itself instead of slithering in a serpentine line like most snakes. This behavior allows it to quickly cross loose sand and climb steep dunes without slipping. While they also travel over hard soil, they live near loose sand to bury themselves up to their protruding eye scales where they lie and wait for prey. Juveniles wiggle their tails to convincingly mimic the movements of moths, which attracts their lizard prey.

- Northern Black-tailed Rattlesnake from Tucson

You can encounter rattlesnakes several different ways. Sometimes they just pass by if you spend time in the right spot. I usually find then by hiking up washes or road-cruising at night. Road cruising is when you slowly drive on outlying roads at night and spot animals crossing in your headlights. You see all sorts of animals while road-cruising. Besides herps, I see Owls, Javelina, Deer, Tarantulas, and Ringtails. Nighthawks cleverly flew ahead of my truck withing the beams of my headlights to catch moths.

Photographing Hummingbirds in the Sonora Desert

I devoted this separate blog to my adventures photographing hummingbirds. Southeast Arizona has the most hummingbird species in the US. I visited several hummingbirds sanctuaries in Sierra Vista and Madera Canyon along my trip. The technical challenge of capturing sharp birds in flight was an extremely fulfilling technical challenge.

Strange Lights in the Sky West of Tucson

On Aug 8th of my trip, my friend Michael and I were shooting monsoon lightning over the Santa Rita Mountains. We saw a strange light growing in the western sky about 30 minutes after sunset. It began as a small bright spot that looked like a search light and rapidly expanded into a huge, glowing cloud that filled the entire western heaven. Michael swiveled his camera and shot the quickly changing apparition without having time to dial in his settings. It then quickly receded and disappeared. To the naked eye, it appeared white, but the camera captured a rich spectrum of colors. Given that new technologies are emerging fast, and we were surrounded by military bases, we pondered whether this was some kind of test.

I researched what this could have been for a few weeks before arriving at a possibility. Several celestial phenomena roughly fit the description including Noctilucent Clouds, the Zodiacal Light and Gegenshein, but none matched perfectly. A friend suggested that this was actually the launch of the Space X Falcon 9 rocket delivering a payload of Star Link satellites. There was a Space X launch west of our location at Vandenberg Space Base, CA exactly when we witnesses the cloud. At first that didn’t make sense because a rocket launch is normally a bright streak, not a glowing cloud. Then I learned about the Twilight Effect. This phenomenon occurs when a rocket is launched in the west, exactly 30 minutes after sunset or before sunrise. Light from the low angle sun catches the rocket exhaust in the upper atmosphere where it has expanded into a wide cloud. Mystery apparently solved.

Arizona has the best Sunsets and Gila Monsters

Something strange happens during sunset in the Sonora Desert that I’ve seen nowhere else; red afterglow occurs while the sun is still up. Afterglow is when the clouds ignite into warm, fiery colors. In most regions, this doesn’t happen until well after sunset. Afterglow normally occurs because the already set sun is still sending light rays through the Earths atmosphere from a very low angle below the horizon. At this angle, the light must pass through a longer distance of atmosphere than when the sun is directly overhead. As it travels through the atmosphere, the blue wavelengths are filtered out, leaving only warm hues. In southern Arizona, the apparent reason for early afterglow is because fine dust from the dry desert hangs in the upper atmosphere, which filters out the blue wavelengths.

Wanting to photograph monsoons, sunsets and herps, I was often scrambling to capture them all at once because each often arose in the evening. While shooting the sunset above, a monsoon was brewing over my shoulder, a Horned Lizard scurried past and then a Gila Monster appeared on the trail in the foreground.

I frantically switched from my landscape configuration to nighttime macro to catch up with this Gila Monster. In my experience, they never stop moving so I consider myself lucky to have nabbed the portrait of him tasting my scent with his tongue.

They release potent neurotoxin from glands in the mouth when they bite that flows through grooves in the teeth. There, it mixes with the saliva and they chew the venom into their prey. While the venom itself is highly toxic, they only release a small amount that isn’t permanently damaging to humans. Moreover, it’s shockingly difficult to get bit by this slow, clumsy, docile species in the wild.

Most documented bites occur in captivity. The few recorded deaths happened in American antiquity, likely from infected wounds and not the venom itself. The bite, as described by pet owners on YouTube, apparently hurts worse than a rattlesnake bite, but subsides with no effects within a week. Now, how have you been bitten by both Rattelsnakes and Gila Monsters to know that?

The Regal Horned Lizard looks like a chiseled sculpture. Even the rich earth tones of its camouflage gradually feather into one-another. They’re very slow moving for lizards. If they’re camouflage fails, they posses the odd defense of squirting foul tasting blood from their eyes.

The Sacramento Mountain Salamander

My first stop en route to Arizona were the Sacramento Mountains in south-central NM to see an anomalous species of salamander. The Sacramento Mountain Salamander is a member of the family Plethodontidae-small woodland salamanders that live and breed entirely on land and require moist woodlands to survive. This salamander is found nowhere else and subsist only in the moist, evergreen forests on these peaks. Only a 20-minute drive below delivers you to hot NM desert where no woodland salamander can survive. The nearest large populations of Plethodontine salamanders occur hundreds of miles away in the moist climates of the eastern US and west coast.

It’s unlikely that a relict population of these salamanders could endure for tens of millions, or even tens of thousands of years on these peaks through climactic and geological change without becoming extinct. Their isolation may be explained by the burgeoning Younger Dryas Impact Theory. In posits that the climate and ecosystems of Earth were drastically different from today, only a few thousand years ago. Lush forests grew in regions that are today desert. A disintegrating meteor impacted a broad area of the planet. This punctured the Earth’s crust, burned forests, and melted the polar ice caps instantly. The Great Flood ensued, along with global cataclysms that deleted most life on Earth. The increased water volume and reduced sunlight from particulates cooled the atmosphere, causing a very brief ice age. The glaciers sculpted the contemporary landscape that we know today as they receded.

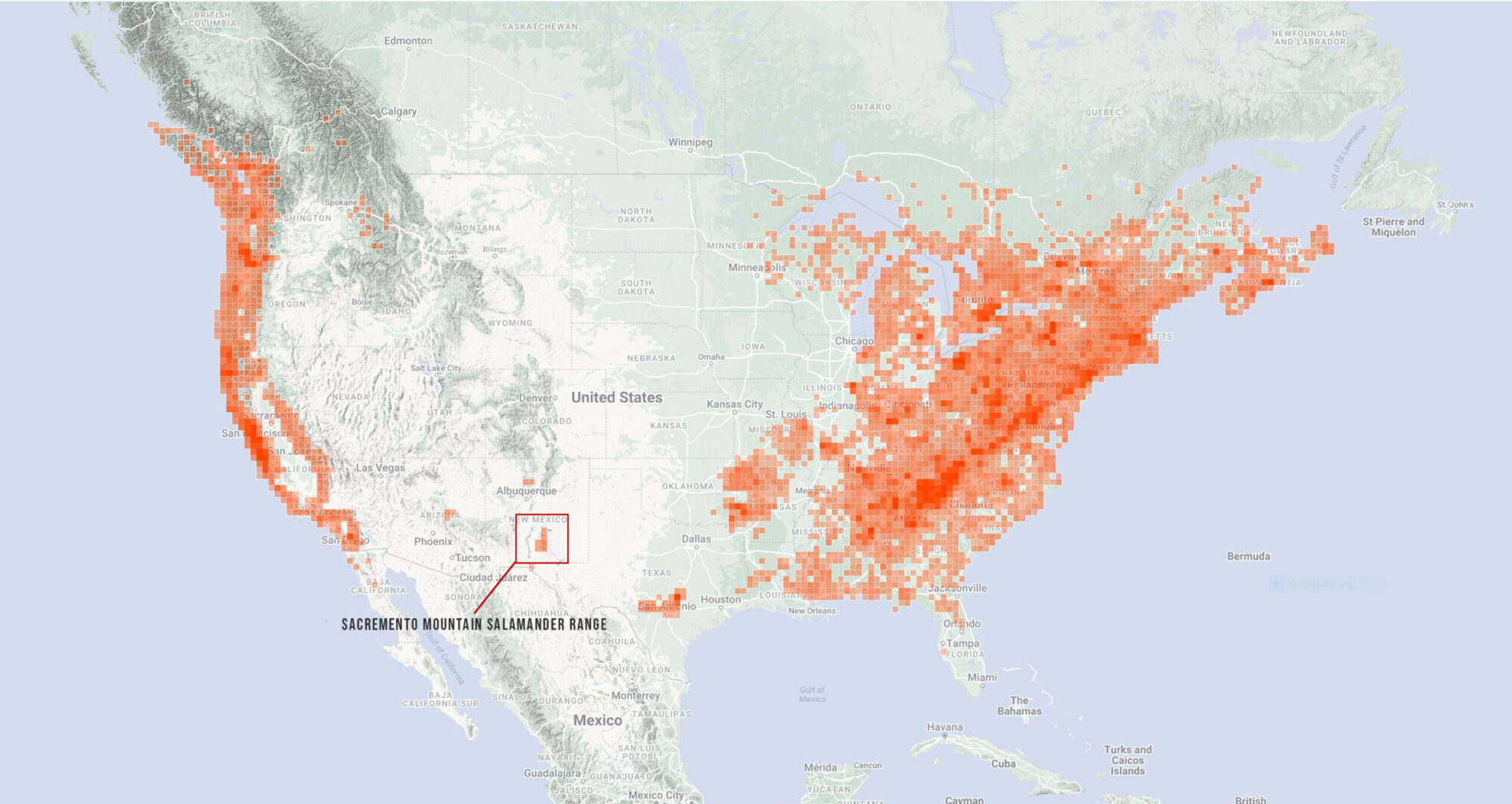

Before this complex of events, Plethodontine Salamanders theorettically occurred from coast to coast, occupying the gap in the map below when it was temperate forest. After the ice age, a few salamanders remained on the Sacramento Mountains.

- This map from iNaturalist shows the range of all Plethodontine salamander species, with the Sacramento Mountain Salamander’s range isolated in the box.

The Saguaro Cactus and the Spiny Web

- Like rows of big, plastic trees, a Saguaro forest sprawls in front of Picacho Peak

In a preposterous scene from Oceans 12, Vincent Cassel’s character performs an extreme game of limbo to maneuver his way through a field of overlapping lasers to make a heist. This is what walking through the Sonora desert is like. Spiny plants cross-cross each other at every height. To make it through without being punctured you must contort yourself like a slinky. You can’t, however, actually make it through without being punctured.

There are plants with long, stiff spines. There are ones with spines growing out of spines. There are spines with hooks. There are even big spines that impale you, then embed microscopic spines within you. The Jumping Chola Cactus grows spine grenades that dangle from the mother plant and attach to passers by with the slightest graze. Its spines are long and stiff, appearing as if they can simply be pulled off with your fingertips. But the spines are covered in microscopic barbs that embed in fingertips. To remove them you must inevitably rip holes in your flesh. I needed my multi-tool pliers to perform several rounds of spine-grenade removal.

The Saguaro Cactus is a remarkable organism with almost unbelievable characteristics. Being surrounded by a Saguaro forest always feels surreal. They commonly grow up to 40ft tall, with a record of 76ft. They can live over 200 years and may not grow their first arm until 100 years old. At 10 years, they’re still barely noticeable spikes a few inches tall. Old ones have seen so much history that it’s truly a shame for them to be wantonly cut down. The accordion-like ridges on their skin allow the Saguaro to expand to absorb and store water. Their water-tight skin feels like synthetic plastic. Saguaros flower from April to June and close during the day in the hottest part of the season. The shape of the flowers is particularly adapted for pollination by the Long-nosed Bat at night, though it has many other pollinators. The Saguaro is a keystone species of the Sonora Desert, providing food and shelter to numerous species.

Toads and Frogs of the Sonora Desert

- After years of searching various locations around the southwestern US I finally found a Chihuahuan Green Toad. I think they’re the most beautiful North American toad, and diminutive at less that 2″ long

Counterintuitively, I often encounter a greater diversity of Anurans on the move at night in the Sonora Desert than most temperate regions that I’ve visited. Some of them are unique in extremely peculiar ways. The gargantuan Sonora Desert Toad, for example, is America’s largest toad at up to 8″ and weighing over 2 pounds. When you pick one up, its blubbery folds roll over your hand like a water bottle. Their mouth is an indiscriminate consumption machine willing to devour anything small enough to fit, including snakes, rodents, tarantulas and scorpions. Paratoid glands on several parts of their body release a highly toxic poison that’s responsible for killing more domestic dogs that rattlesnakes do. The poison is exuded when pressure is put on the glands. They’re habitat generalists that I encountered everywhere from lowland desert scrub to the mountain sides of the Sky Islands.

- Great Plains Toad

- Chiricahua leopard frog

- Sonora Desert Toad

- Couch’s Spadefoot Toad

- Red-spotted Toad

- Canyon Treefrog

Large Sonoran Arachnids and Impregnable Earth

- The Desert Hairy Scorpion takes up nearly the palm of my hand, but the sting is reported to be less painfull than a wasp

The ground of the Sonora Desert is riddled with holes of all sizes where creatures live to escape the heat. Just after dusk is a good time to see what inhabits them. Tarantulas, Scorpions and other arthropods were sitting in the entrance of their holes, waiting to emerge. The Vinegaroon is a false scorpion that, rather than stinging, has the most peculiar ability to spray acetic acid from the tip of its abdomen to repel predators. The Wind Scorpion is another false scorpion that possesses the largest mandibles relative to body size of any animal. The jaws of its mandibles look like two scorpion pincers placed on its mouth. An amazing quality of all these fossorial arthropods is their ability to excavate burrows in the hard Sonoran soil.

On a previous trip to Tuscon I sat next to a guy at a breakfast bar who started talking to me. In his rambling, he claimed that before reforming his life, he was once involved in drug trafficking and had to bury a few people in the desert. As he spoke of murder, I could only think, “how could he possibly have dug in the hard Caliche soil? The Sonoran soil is called Caliche, which is comprised of deposited Calcium carbonate. This is a main ingredient of cement. It’s amazing that arthropods and other animals can somehow tunnel thier way meters deep through this rock-hard substance.

- Funnel-web Wolf Spider

- Tahono Vinegaroon

- Desert Blond Tarantula

- Wind Scorpion

Roadrunners: The Lizard Hunters

This male Greater Roadrunner has captured a Spiny Lizard that he’s about to share it with his girlfriend, waiting out of the frame. A Roadrunner carrying a lizard is no rare site. These sleek harpoons with legs are designed to deftly maneuver through spiny cacti and catch fast moving prey. They’re able to snatch rattlesnakes and scorpions with impunity, bash them against the ground and devour them whole. The Roadrunner is like a small Velociraptor. They were present in all lowland Sonora habitats that I visited. Even when I couldn’t see them, I constantly heard them. They make different cooing sounds, and also an interesting bill rattle sound, which is a high frequency clicking.

Trail by Fire

Navigating to this spot in the Santa Rita Mountains was literally a near death experience, but an exciting one. I trusted Google Maps to get me here, but it lead me down a sandy desert road that apparently no longer really exists. It was navigable for about 5 miles before the road simply stopped. In front of me was just raw desert scrub with a lingering hint of where the road once continued. Turning around would require back-tracking and wasting time. My paper map claimed that I’d meet a road if I continued straight through the desert for another 1/2 mile. A monsoon thunderstorm brewed overhead was cast lightning strikes. I drove forth with branches and spines scraping my paint while driving circuitously through narrow gaps between thorny bushes. I reached the road, but to my dismay it was on the other side of a locked gate. I executed an 8-point turn to head back in the direction from which I came.

Navigating to this spot in the Santa Rita Mountains was literally a near death experience, but an exciting one. I trusted Google Maps to get me here, but it lead me down a sandy desert road that apparently no longer really exists. It was navigable for about 5 miles before the road simply stopped. In front of me was just raw desert scrub with a lingering hint of where the road once continued. Turning around would require back-tracking and wasting time. My paper map claimed that I’d meet a road if I continued straight through the desert for another 1/2 mile. A monsoon thunderstorm brewed overhead was cast lightning strikes. I drove forth with branches and spines scraping my paint while driving circuitously through narrow gaps between thorny bushes. I reached the road, but to my dismay it was on the other side of a locked gate. I executed an 8-point turn to head back in the direction from which I came.

I made it back through the scrub, but when I reached the dirt road, the desert was suddenly on fire! The scrub on both sides of the road was ablaze and spreading ahead of me like an ocean tide. Clearly the only option was to drive forward like a rally racer and hope that I didn’t get halted from high flames or burning debris laying across the trail. I caught up with the boundary of the fire and and drove out of it like the Millennium Falcon bursting out of the exploding Death Star. I called 911 to alert them to the fire.

Once back on track, I barely reached my destination in the Santa Rita Mountains by sunset. From my vantage point above, I could see down to where I was. The smouldering fire had burned itself out and emergency vehicles were near.

The Mouse-devouring Lizard

Though I hiked and drove many miles through the Sonora Desert to find interesting creatures, I encountered a particularly bizarre sight while sipping ice water on a friend’s patio in Phoenix. This bruiser of a male Desert Spiny Lizard walked by with a Pocket Mouse shoved in its mouth. I ran out to my truck to grab my Camera and 100-400mm lens. Amazingly, the lizard was still there when I returned. This picture is testament that most reptiles & amphibians simply consume any animal they can catch and swallow, regardless of taxa. Males of this rugged species also engage in brutal combat over territory, biting and flipping each other.

Diverse Sonora Insects

- Arizona Net-winged Beetle

The insects in southern Arizona are generally larger and more colorful than what I’m used to elsewhere. It’s also a cross-roads of insect diversity, particularly for migratory moths. In the Santa Rita Mountains, I’ve run into researchers attracting nocturnal insects with light traps. Give me a Yucca in bloom and I’ll show you a microcosm of diversity. In the southern Chiracahua Mountains I spent hours photographing multiple species on a single Yucca. Pollinators and herbivores feeding on the Yucca in turn attracted various predatory insects. Closely inspecting the flowers and undersides of the fronds yielded one species after another. I used the Venus Laowa 2x 90mm macro lens because it renders 2:1 magnification without modification. Even at f/16 the images were startling sharp for such an inexpensive lens. For illumination I used a Godox TT 350 flash with a pop-up flash diffuser.

- Light Trap

- Bee Assassin

- Matis

- Robber Fly

- Black and Red Stripe Blister Beetle

Red-banded Snake Mimics

The Sonoran Coral Snake’s venom is an extremely potent neurotoxin. However, there are no human fatalities recorded because this tiny snake, essentially, doesn’t bite. Herpers shouldn’t take this as license to handle them or you might be the first statistic. For venom to be effective it must be injected into the blood stream via fangs, which act like hypodermic needles. Technically, venom can be swallowed with no ill effects. The stomach simply disassembles the venom into its constituent elements.

The Coral Snake’s festive coloration is thought to be aposomatic warning to would-be predators that it possesses deadly venom. Framed with yellow and black, the red band is more visible. There are several harmless snakes in the Sonora Desert with red bands that mimic the Coral Snake. The only one that I found was the Long-nosed Snake in the same area as the Coral Snake. The classic example of Batesian mimicry is the Sonoran Mountain Kingsnake, which I didn’t find. You can distinguish them with the aphorism, “Red touches black, venom lack. red touches yellow, kill a fellow”.